5.I INTRODUCTION

The

discussion in Chapter 4 concerned the market-area

or supply-area patterns of activities in which there is strong spatial

repulsion among the individual units. In sharp contrast, however, other

activities show highly clustered patterns.

Cluster is,

of course, the logical pattern for units of an output-oriented activity whose

markets are concentrated at one or a few locations, and correspondingly for

units of an activity oriented to inputs whose source locations are few. There

is a high concentration of producers and suppliers of such theatrical inputs as

actors, stage designers, and theatrical makeup specialists in Los Angeles and

New York because so much movie making and theater activity is concentrated

there. The making of vintage wines is confined to the relatively few areas

where the right kinds of grapes will flourish.

There are

other situations, however, where the basis for clustering is the mutual

attraction among the competing units of a particular activity, and this

attraction outweighs any repulsion that might arise from their rivalry. Thus a

frequent practice of chain-store firms is to locate branch stores as close as

possible to a competitor’s branch store. A tendency toward agglomeration

is unmistakable in the juxtaposition of car sales-rooms along "automobile rows"

and in the formation of financial districts, nightlife districts, civic

centers, produce markets, and high-class shopping areas in cities. The larger

the city, the more specialized and numerous are such neighborhood

agglomerations. In New York, large advertising agencies are so clustered along

a section of Madison Avenue that the street has given its name to the industry.

Similarly, a section of Seventh Avenue is preempted by the garment trades, part

of Forty-seventh Street by diamond merchants, and so on for many other

specialties. The common feature of all such clusterings is that each unit finds

the location good because of the presence of the others. There is a

positive mutual attraction rather than a repulsion. The explanation of

such mutual-attraction clusters lies in special characteristics of the activity

itself, its markets, or its suppliers.

5.2 EXTERNAL ECONOMIES: OUTPUT VARIETY AND MARKET

ATTRACTION

In some

activities, the basic reason for the agglomerative tendency is that the outputs

of individual units are not standardized; they are not perfect substitutes for

one another, and moreover, they differ in such manifold and changing ways that

they cannot be satisfactorily compared by the buyer without actual inspection.

The locational significance of this characteristic can best be seen by a pair

of contrasting examples.

A

manufacturing firm buying sheet steel simply decides on its specifications and

then finds out which steel producer will give the best price and fastest

delivery. A visit to warehouses or rolling mills to look over the sheets and

make a selection is unnecessary, because the specifications themselves (plus

conceivably a sample sent for testing in the buyer’s plant or laboratory)

fully identify the characteristics of the steel. Consequently, the transfer

costs involved are those of shipping the steel from producer to user, and there

is nothing in the situation that would make it desirable or convenient for the

rival sheet steel producers to be concentrated in one place.

Contrast

this with a man or woman buying a car or a new hat, a department store

selecting its line of fall fashions, or a fashion designer searching for

something simply devastating in novelty buttons. In any of these cases, the

buyer does not know exactly what will be purchased. He or she will be selecting

one item (in the case of the car) or maybe more (in the case of the hat) or a

very large number (in the case of the department store’s fall line). The

items cannot be adequately described in a catalog, and it would be much too

expensive and time consuming for the producers to supply each prospective buyer

with a full set of samples. Under these circumstances, the "demand" is not so

much demand for specific items as it is demand for a varied display of

products; and the wider the variety presented at a particular location, the

more demand that location will attract.

Therefore

the buyer makes a shopping trip, preferring the largest display center

accessible to him. The more he is prepared to spend, the farther he will be

prepared to go in the interest of variety. Thus most of us would be willing to

journey farther out of our way to select a camera than a necktie; still farther

to select a new car; and still farther to select a job with career

possibilities.

It is clear

that the activity that is presenting the displays will tend to adopt a

clustered pattern, with its units positively attracting one another. A newcomer

to the cluster may even be welcomed, because that seller will enrich the

variety and draw still more demand to the location.

It should

be noted also that where comparison shopping is important, the significant

transfer costs are borne by the buyer, and the major element in transfer costs

is personal travel time. The transfer of the goods bought may be handled by the

buyer himself (he may drive his new car home or carry his other purchases). In

any event, however, the transfer cost is not enough to counteract the advantage

(to both buyers and sellers) of having the selling units

agglomerated.

When the

purchases are transferred separately, it is of course feasible to separate

production or delivery, or both, from display. Thus new car dealers sometimes

have to order from the nearest assembly plant after the buyer has made his

choice; and in recent years more and more garment producers have moved their

factories out of the city in order to reduce production costs, and maintain in

the city only the functions of display and associated entertainment for the

out-of-town buyers.

These

examples illustrate one important kind of external economy of agglomeration of an activity—"external" to the individual unit involved because the

advantages depend on how many other units of its type are joining it to make a

cluster that attracts demand.1

5.3

EXTERNAL ECONOMIES: CHARACTERISTICS OF THE PRODUCTION PROCESS

5.3.1 Introduction

The

externalities associated with the size of a cluster are by no means limited to

those that enhance demand as a result of the characteristics of shopping

behavior. Some closely analogous external economies of agglomeration involve

cost and supply considerations, and these tend to affect many of the same

activities.

If products

are complexly differentiated and changeable from one day or week to the next,

the chances are that at least some of the inputs also share those

characteristics. Thus a fashion garment shop will have a constantly changing

need for different fabrics, thread, buttons, zippers, and the like. With the

nature of the output continually changing, manpower needs can vary

unpredictably and suddenly; with speedy delivery at a premium and production

scheduling intricate, equipment repairs and parts must be quickly available.

Since perhaps the most important task of the manager is to estimate what the

buyers will want and what his or her rivals will offer, a crucial input is

fresh information, gathered largely by mixing with the right people and keeping

the eyes and ears open.

Every one

of these input requirements, plus others, is best satisfied in a tight cluster.

The basic reason can be made clear by the following example. Suppose we have a

small plant that manufactures ladies’ coats. A long sequence of separate

operations is involved, including such operations as cutting and binding the

buttonholes. Specialized equipment exists for making buttonholes rapidly and

cheaply in large quantities, but it represents a sizable investment. Individual

coat manufacturers would not find it worthwhile to invest in such a machine,

since they could not keep it busy all the time; they have to resort to making

their buttonholes in a slower way, involving greater labor cost. However, if

they locate in a cluster with enough other clothing manufacturers, their

combined need for buttonholes may suffice to keep at least one of the

specialized buttonhole machines reasonably busy. Then a separate firm

specializing in buttonhole making joins the cluster. The clothing manufacturers

contract that operation out to that firm, to the advantage of all concerned,

including the customer who gets the coat cheaper.

This

example can be extended to embrace dozens of other individual operations that

likewise can be delegated to specialized firms when there is a cluster,

enabling a sufficient number of firms using the specialized service to enjoy

convenient access to the specialist.

5.3.2 External Economies and Scale

Some highly

significant facts emerge from this discussion. First, we have explained an external economy for the clothing manufacturers in terms of the internal economies entailed in specialized operations (the

buttonhole-making establishment and other such auxiliary suppliers must have at

least a certain minimum amount of business or they cannot cover their fixed

costs). Second, the result of the mutually beneficial symbiosis of the garment

makers and the buttonhole maker is that the former are now also more

specialized. They are confining themselves to a narrower range of operations,

and for any given level of output of coats they will have smaller plants and

fewer employees; that is, the productivity of inputs will be enhanced.

There is another advantage in this. The principal constraint on the size of

their plants is the complexity of management decision making in an industry

where the products are continually changing (in response to or in anticipation

of a volatile demand), orders are small, and the production cycle is of

extremely short duration; specialization should enhance efficiency here as

well. A further constraint, in many cases, is the supply of capital for the

individual entrepreneur.

For a given

establishment or firm, these gains in production efficiency may be illustrated

graphically by reference to Figure 5-1. If, as the

result of specialization, the location unit within an activity cluster can take

advantage of internal economies of scale, subsequent increases in productivity

will move the unit down along its average total cost curve. Thus in panel (a)

of Figure 5-1, location within the cluster has made it possible to increase the

rate of output from Q0, to Q1, with a consequent decrease in average total costs

from ATC()to ATC1.

The

increased efficiency in production that results from the cluster of activity

may show up also as a decrease in average total costs at each rate of

output. As shown in panel (b) of Figure 5-1, this would imply a downward

shift in costs from ATC to ATC’. Such a change could stem

from several sources. For example, if scale economies are achieved by members

of the cluster, the products and services they produce will be available to all

buyers at lower cost. Hence the per unit cost of inputs will fall for any buyer

using their outputs, including those buyers who are also members of the

cluster. Similarly, any savings in transfer costs realized by members of the

cluster would have the effect of lowering average total costs. Other such

sources of economies might include the ability of group members to maintain

smaller inventories in the face of demand or supply uncertainties, increases in

labor productivity resulting from specialization in the work place, or

increased efficiency in management and organization.

It is also

important to note that in an industry where these agglomeration economies are

realized, there is little or no rationale for the development of multiplant

firms. As we have pointed out, the economic size of the individual plant in

such industries is effectively limited by the problems faced by management.

There is no point in the firm’s establishing branch plants; all the

activity is at one location, and the management must constantly give close

attention to what is going on inside the plant. This situation contrasts

sharply with that of a business such as food retailing, where the constraint

upon the size of an individual store is the maximum size of its market area

(reflecting transfer costs). The multistore firm enjoys great advantages in

mass purchasing, advertising, research, financing, and management; the optimum

firm size far exceeds optimum store size.

In summary,

we can distinguish three levels at which economies of size appear in respect to

any particular activity.2 These are (1) economies

associated with size of the individual location unit (plant, store, or

the like); (2) economies associated with the size of the individual firm; and (3) economies associated with the size of the agglomeration of that

activity at a location. We can refer to these, for brevity’s sake,

as unit, firm, and cluster3 economies, and the size at which each of these economies peaks can be thought of as

the optimum unit size, the optimum firm size, and the optimum cluster

size.4

These

optima are determined by the characteristics of the activity, including its

locational sensitivity to transfer costs and other locational factors. When

firm optimum is larger than unit optimum, there are multiunit firms with

operating branches, ordinarily in different locations, as in retail chains and

some kinds of manufacturing. Otherwise, the single-unit firm is the norm. When

cluster optimum exceeds the optimum for units or firms, there are multiunit

and/or multifirm clusters of the activity; otherwise, separate locations are

the norm, as is illustrated by primary processing plants for farm or forest

products.

5.3.3 Lichtenberg’s Study of "External-Economy

Industries"

The classic

analysis of the clustering of certain manufacturing industries on the basis of

agglomeration economies external to the individual location unit and firm was

made in the late 1950s by Robert M. Lichtenberg for the New York Metropolitan

Region Study. Table 5-1 (below) lists the 87 industries that he identified as

dominated by external-economy factors of Location and that are relatively

concentrated in the New York metropolitan region.

| TABLE 5-1: Manufacturing

Industries Relatively Concentrated in New York City by External Economies,

1954 |

|

Industry |

New York Metropolitan Region’s Share of Total U.S.

Employment (percent) |

|

Hatters’

fur |

99.9* |

|

Lapidary

work |

99.5* |

|

Artists’

materials |

91.9* |

|

Fur goods |

90.4 |

|

Dolls |

87.4* |

|

Schiffli-machine

embroideries |

86.5 |

|

Hat and cap

materials |

85.7 |

|

Suspenders and

garters |

84.7* |

|

Women’s

neckwear and scarves |

84.7 |

|

Hairwork |

82.7* |

|

Embroideries, except

Schiffli |

80.0 |

|

Tucking, pleating,

and stitching |

76.8 |

|

Handbags and

purses |

75.6 |

|

Tobacco

pipes |

75.3 |

|

Millinery |

64.7 |

|

Children’s

coats |

61.6 |

|

Belts |

60.9* |

|

Artificial

flowers |

60.6 |

|

Women’s suits,

coats, and skirts |

58.8 |

|

Dresses, unit

price |

58.7 |

|

Furs, dressed and

dyed |

56.9* |

|

Umbrellas, parasols,

and canes |

54.5* |

|

Robes and dressing

gowns |

54.3 |

|

Small leather

goods |

53.1 |

|

Miscellaneous

bookbinding work |

53.0* |

|

Handkerchiefs |

49.8* |

|

Buttons |

49.5 |

|

Trimmings and art

goods |

49.0 |

|

Men’s and

boys’ neckwear |

48.3 |

|

Watchcases |

48.1* |

|

Phonograph

records |

48.0* |

|

Books, publishing

and printing |

46.8 |

|

Periodicals |

46.5 |

|

Lamp

shades |

46.0 |

|

Corsets and allied

garments |

45.9 |

|

Children’s

outerwear, n.e.c+ |

43.2 |

|

Knit outerwear

mills |

42.3 |

|

Blouses |

41.7 |

|

Finishing wool

textiles |

41.5 |

|

Bookbinding |

41.1 |

|

Jewelry |

40.5 |

|

Suit and coat

findings |

39.6 |

|

Costume

jewelry |

39.5 |

|

Children’s

dresses |

39.3 |

|

Men’s and

boys’ cloth hats |

38.0 |

|

Waterproof outer

garments |

37.6 |

Printing ink |

34.7 |

Coated fabrics,

except rubberized |

34.5* |

Women’s and

children’s underwear |

34.4 |

Luggage |

34.3 |

Apparel,

n.e.c. |

34.0 |

Needles, pins, and

fasteners |

33.8 |

Jewelry and

instrument cases |

33.7 |

Engraving and plate

printing |

33.6 |

Miscellaneous

publishing |

33.3 |

Curtains and

draperies |

32.9 |

Typesetting |

32.9 |

Straw hats |

32.8* |

Women’s

outerwear, n.e.c. |

32.7 |

Jewelers’

findings |

32.6* |

Games and toys,

n.e.c. |

32.1 |

Engraving on

metal |

30.4 |

Leather and

sheep-lined clothing |

30.4 |

Textile products,

n.e.c. |

30.4 |

China decorating for

the trade |

29.0 |

Housefurnishings |

28.9 |

Photoengraving |

28.2 |

Book

printing |

25.5 |

Electrotyping and

stereotyping |

25.5 |

Fabric dress

gloves |

25.3 |

Greeting

cards |

25.2 |

Galvanizing |

24.4* |

Candles |

23.5 |

Mirror and picture

frames |

22.7 |

Men’s and

boys’ suits and coats |

22.3 |

Knitting mills,

n.e.c. |

21.2 |

Finishing textiles,

except wool |

20.6 |

Signs and

advertising displays |

20.4 |

Plating and

polishing |

18.7 |

Knit fabric

mills |

18.3 |

Lithographing |

17.9 |

Enameling and

lacquering |

16.7 |

Statuary and art

goods |

16.6 |

Commercial

printing |

16.5 |

Felt goods,

n.e.c. |

16.0* |

Narrow fabric

mills |

15.4 |

Dresses,

dozen-price |

12.9 |

*Approximate

figure estimated by Lichtenberg: exact figures unavailable because of Census

disclosure rules.

+n.e.c.: not elsewhere classified.

Source Robert M. Lichtenberg, One-Tenth of a Nation (Cambridge, Mass.:

Harvard University Press, 1960), pp. 265-268; based on data from U.S. Census of

Manufactures, 1954.

"Relatively

concentrated" means that the region’s share of national employment in the

industry exceeded 10.4 percent—which was the region’s share of total

national employment and accounts for the title of Lichtenberg’s

book.5

Lichtenberg’s study provides documentation and illustration on

some of the points we developed earlier. Table 5-2 sums up some salient characteristics of those manufacturing industries that he

rated as least affected by transport orientation. It covers, in his words, "all

industries for which the dominant locational factor is inertia, Labor, or

external economies, and those for which no dominant locational factor could be

assigned." It is clear from this tabulation that prevalence of single-unit

firms (which we previously noted as a characteristic of industries clustered

because of external economies) is associated with small size of plant, high

labor intensity (as suggested by small energy use per worker), and (for

consumer goods industries) small inventories implying fast turnover.

Table 5-3 examines the relation between degree of

concentration in New York and proportion of single-plant firms, in the same set

of industries as in the preceding table. Industries most heavily clustered in

the New York metropolitan region are consistently characterized by a prevalence

of single-plant firms. In other words, New York as the chief metropolis of the

nation appears to have strong special attractions for industries of the

single-plant type, which, as Table 5-2 showed, are

characterized by small units and high labor intensity.

Table 5-4 compares average plant size (number of

employees per establishment) in the New York metropolitan region and in the

United States as a whole, for different classes of industries. In

transport-sensitive industries selling to national markets (the first row of

figures in the table), the situation is roughly as follows: New York plants are

larger than plants elsewhere in industries that show a definite tendency to

concentrate in New York (that is, the region has more than 20 percent of

national employment). This relationship seems to make sense. In a

market-oriented industry, we should expect that the main centers of the

industry would have the largest plants, since they are the locations with best

access to markets, and the economic size of plants in such industries is

constrained primarily by the added transport costs involved in serving a wider

market area. In addition, at least four of the transport-sensitive

national-market industries6 most heavily

concentrated in New York (chewing gum, rattan and willow ware, copper refining,

and cork products) use imported materials, and New York’s status as a

major port of entry helps to explain its advantage.

The

external-economy industries, which are nearly all rather highly concentrated in

the New York region, show a significantly contrasting size relationship.

Despite the great prominence of New York as a location for such industries, the

plants there are smaller than those elsewhere. This should be expected

according to the considerations already discussed. A plant of an

external-economy industry located in New York is in a position to contract out

more operations to specialists, such as our buttonhole maker. Within any Census

industry classification, those firms and plants that to the greatest degree

share the special characteristics of clustered external-economy activities

(such as variable demand and product, rapid production cycle, and low degree of

mechanization) will be the ones most likely to find the New York location

attractive; and those characteristics are, as we have seen, strongly associated

with small plant size. Plants in the same Census industry located elsewhere are

more likely to be turning out a less variable kind of product, and their

optimum plant size is somewhat larger.

Thus

industries of the clustered type have, as a class, the peculiar characteristic

of operating in smaller units (in terms of both plant and firm) in locations of

major concentration than they do elsewhere.

5.4 SINGLE-ACTIVITY CLUSTERS AND URBANIZATION

5.4.1 Introduction

The

advantages of a clustered location pattern for certain types of activities are

now apparent. But what does such a cluster contain besides the major

beneficiary of those advantages?

There are

certainly some types of clusters that need contain nothing else—for

example, "automobile rows." Here the mere juxtaposition of a number of

salesrooms makes the area attractive to prospective buyers, and that is the

basis of the agglomeration tendency. The same is true for many other types of

single-activity neighborhood cluster in cities, such as art shops, antique

stores, secondhand bookstores, wholesale and retail produce markets, and the

like.

But in each

of those cases, what really draws the buyers is variety. There would be no

advantage in agglomeration (so far as buyers are concerned) if the wares of the

different sellers were identical. Accordingly, still other product lines or

activities may contribute to the advantage of the cluster, provided they offer

something that the same buyers might want to pick up on the same trip. In this

way, the attractions of a cluster of high-fashion dress shops may well be

enhanced by the addition of a shop specializing in high-fashion shoes or

jewelry, or even a travel agency catering to high-income travelers. At a more

plebeian level, the familiar suburban shopping center includes a wide

assortment of retail trade and service activities. The developers of the center

usually plan rather closely in advance the kinds of businesses to be included

and take pains to pin down at least some of the key tenants (such as a

department store branch, a bank, or a movie theater) even before ground is

broken. Other relatively broad and diverse clusters based on the attraction of

a common demand are recreation centers and cultural centers.7

Just as

externalities associated with shopping behavior imply advantages for clusters

of closely related activities, a cluster in which availability of common

inputs plays an important role (such as in the external-economy industries

analyzed by Lichtenberg) is also more likely to be a complex of closely

related activities than just a clump of units of one activity. Thus an

essential part of a cluster that is advantageous to garment manufacturers is a

variety of such related activities as machine rental and repair; designing;

provision of special components such as buttonholes, fasteners, and ornaments;

trucking services; and so on. Indeed, the Lichtenberg list includes such

ancillary activities indiscriminately along with the producers of garments and

other final products; this is quite fitting, since it is the tightly knit

complex of activities that yields the external economies that help motivate the

cluster.

5.4.2 Urbanization Economies

Our

examples suggest that the process of identifying an activity cluster is

somewhat more complicated than might first appear. Detailed examination of a

large activity cluster discloses that while some constituent activities (such

as buttonhole making) are so specialized that they are locationally associated

with just one line of activity, others (such as trucking or forwarding

services, entertainment facilities for visiting buyers, and a variety of

business services) are not so restricted. They are essentially elements of a

large urban agglomeration. Their presence, and the quality and variety of the

services they offer, depend more on the size of the city than on the

size of the local concentration of any of the activities they serve.

Economies

generated by activities and services of this sort are external to any

single-activity cluster, but they are internal to the urban area. There is a

parallel to be drawn here to the relationship between a single-activity cluster

and its constituent units. In that instance, economies were realized by the units as the size of the cluster increased; thus economies are

internal to the cluster but external to the unit. In the case of urbanization economies, we recognize that economies accrue to

constituent clusters as the size of the urban area increases. Thus some of the

advantages that a particular activity gets by concentrating in New York could

not be duplicated by simply having an equal amount of that activity clustered

in, say, Columbus, Ohio—though, of course, it is possible that Columbus

might offer some compensating attractions of a different nature.

There have

been, and still are, some noteworthy multifirm clusters of single activities in

relatively small places (historic examples are glove making in Gloversville,

New York; hat making in Danbury, Connecticut; and furniture making in Grand

Rapids, Michigan). But it is apparent that this type of single-activity cluster

(in which the bulk of an activity is found in a few "one-industry towns") has

rather gone out of style since F. S. Hall proclaimed its heyday in 1900.8 Such concentrations depended heavily on the external

economies of a pool of specialized labor skilled in operations peculiar to one

industry, and often predominantly of one nationality group;9 on a reservoir and tradition of entrepreneurship similarly

specialized; and on the inertial factor of acquired reputation. Technological

changes and enhancement of the mobility of labor and entrepreneurship explain

why such local specialization has become increasingly rare. By contrast,

external economies on the broader basis of urban size and diversity have

remained a powerful locational force.

5.4.3 Measuring Urbanization Economies

The

symbiotic relationships within single-activity clusters or more complex

clusters reflecting urbanization economies have important implications, both

for constituent activities and for the regional economy as a whole. As a

consequence, much effort has been devoted to understanding and measuring

agglomeration economies. Many people concerned with the growth and development

of specific regions have examined the advantages inherent in urban

concentrations, in an effort to understand the factors most relevant to their

region’s prosperity and problems.

Our

examination of agglomerative forces suggests that they may affect an individual

location unit either through market demand considerations or through

modifications of the production process that enhance efficiency. The evaluation

of either or both of these effects entails some challenging

difficulties.

Recent

efforts to measure the extent of urbanization economies have focused on

estimates of the productivity gain accruing to activities that are located in

larger urban areas. They proceed by treating production in urban areas as being

representative of the aggregate production of component activities. For

example, if one were to estimate the aggregate demand for labor in Boston or

Detroit, one would assume that the behavior of this aggregate reflects a

weighted average of labor demand curves associated with all activities in the

city.

Measurements of this sort rest on the belief that the demand for

factors of production is determined by the value of their marginal product,

that is, marginal physical product multiplied by the price of the good or

service being produced. Because of this, the demand for inputs, including

labor, would reflect the advantages of agglomeration economies. Whether the

source of these economies is due to the size of the location unit, firm,

cluster, or urban area, any associated increase in factor productivity would

show up in the urban area’s demand for labor. With this in mind,

researchers interested in measuring agglomeration economies have reasoned that

by the comparison of labor markets associated with cities of different size, it

might be possible to isolate the contribution of urbanization economies to

labor productivity. Further, if it were possible to isolate a measure of aggregate efficiency in production due to these forces, we would also

have a measure of their average effect on the activities that make up

the urban areas in question.10

Reference

to Figure 5-2 will help to explain and reinforce these

ideas. The lines Da and Dbrepresent

estimates of the aggregate demand for labor in two different urban areas, (a) and (b). Dbis that associated with the larger of

the two. It is drawn to the right of Da in order

to reflect the fact that for any given level of employment, the value of

labor’s marginal product is greater in the larger urban area. This

productivity difference remains even after one accounts for differences in the

size of the capital stock and the "quality" of labor between these

areas.

If the two

urban areas faced the same labor supply function, Sl, equilibrium

employment in each would be given by Eaand Eb; labor is hired up to the point where the value of its marginal product

(given by Daand Db) is equal to the wage

rate. Because of this, the total value of goods and services produced in either

urban area is given by the area under its respective labor demand curve, up to

the level of equilibrium employment. Therefore, the shaded area, EaEbcdef is the increase in factor productivity

associated with larger urban size.11

Estimates

of this measure of urbanization economies have varied from study to study, and

a consensus is not easily drawn. The findings of two early research efforts

have gained wide recognition, however, and will serve to illustrate the kind of

results obtained.12

David Segal

obtained estimates of aggregate production functions along with their implied

labor demand functions for 58 metropolitan areas, using 1967 data. A simplified

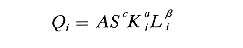

version of the functional form he uses is given by

where Q is output, K is capital stock, and L is employment

(quality adjusted) in city i.13 Technical efficiency is characterized by the multiplicative constant ASc, where S is a dummy variable denoting size, and A and c are parameters. Segal finds constant returns to scale in

aggregate production (a + b=1), and estimates of c are of the

order of .08 for cities with populations of 2 to 3 million. This translates to

an 8 percent productivity gain (the shaded area in Figure

5-2) for metropolitan areas when this population threshold is

reached.

In a study

of fourteen industries also based on 1967 data, Leo Sveikauskas finds that an

average productivity gain of about 6 percent can be expected with each doubling

of city size. He reaches this conclusion by regressing the logarithm of output

per worker (productivity) in a given industry on the logarithm of population

and on an index of labor quality across a large sample of cities. Sveikauskas

recognizes that these productivity differences may be due to differences in

capital intensity across cities; if the ratio of capital to labor (K/L) is large, output per worker will also be large. However, upon investigation

he finds that the variation in capital intensity is not sufficient to account

for the observed productivity differences.

Productivity advantages of this magnitude can mean a substantial

competitive edge. They can be a powerful locational incentive and may well have

played an important role in encouraging shifts in the spatial distribution of

economic activity toward urban areas during much of the postwar period.14

Many

problems confront efforts to measure external economies accruing to activities

in urban areas, and it is important to keep the limitations of related research

in mind. Some types of externalities associated with clusters are not

necessarily related to urban size and are therefore omitted from measurements

of the sort described here. Others are not manifest in productivity differences

at all; rather, they are reflected in demand considerations. Further, because

of data constraints, measurement efforts have been limited to highly aggregate

analysis, whereas many of the most interesting aspects of agglomeration

economies can be appreciated only at a much more micro level. The method

described in this section is nevertheless representative of the kind of

systematic effort that is required to address these and other issues related to

the measurement of this important phenomenon.

5.5 MIXED SITUATIONS

In order to

bring out certain controlling factors, we have been considering sharply

contrasting types of activity location patterns. We have distinguished patterns

dominated by mutual repulsion from those dominated by mutual attraction. We have also distinguished patterns involving market areas from patterns involving supply areas.

It is now

time to recognize that in the real world there are various intermediate stages

between the extreme cases described. In one and the same activity, it is not

uncommon to find (1) dispersive forces dominant at one level of spatial detail

and agglomerative forces dominant at another level, or (2) coexistence of

market-area and supply-area patterns. Let us take a brief look at each of these

types of "mixed" situations.

5.5.1 Attraction plus Repulsion

In any

given activity, the forces of repulsion and attraction among units are usually

both present in some degree, even though one generally predominates. Thus in an

activity characterized by a mosaic of market areas, some of the locations will

have more than one plant, store, or other such unit. Though we think of retail

grocery stores or gasoline stations as primarily mutually repulsive, it is not

uncommon to find groupings of two or more adjacent competitors showing some

degree of mutual attraction. Being at essentially the same location, these

rival units are likely to share the same market area, though one might have a

somewhat wider reach than another. If we think of them as simply sharing "the

market area of that location," the statements made earlier about market-area

determination and pricing policies are still largely valid, except that spatial

pricing systems involving systematic transfer cost absorption become less

feasible when the seller is not alone at its location.15

Similarly,

an activity that we think of as basically clustered, such as the making of

fashion garments, often has several widely separated clusters. Among the

external-economy industries of New York enumerated in Table 5-1, it will be

noted that only a few come close to being exclusively concentrated in

the New York region. The rest are found also in substantial, lesser clusters in

other large cities. One reason for replication of clusters is, of course, that

over long distances transfer costs (in time if not in money) become a

significant constraint on concentration relative to far-flung markets or input

sources. Thus, when we look at the country as a whole, we see a pattern of

market or supply areas showing some force of mutual repulsion among competing

centers. If such an activity is concentrated primarily in, say, New York, Los

Angeles, and Chicago, there will be three roughly demarcated market areas or

supply areas, each shared by all the members of the corresponding cluster. In

this connection, it is much more likely that market areas rather than supply

areas will be involved, since most external-economy activities produce

transferable outputs that need fast delivery to rather widespread markets, and

their transferable inputs come from fewer sources and are of a more staple

character.

5.5.2 Coexistence of Market Areas and Supply Areas, When Both

Sellers and Buyers Are Dispersed

Somewhat

different from the case just discussed is a not uncommon situation in which

there are many selling locations and many markets, and not necessarily any

significant clustering tendencies at all. Sales from one producing district are

distributed over many market points, and at the same time any one market

district buys from many supplying points. The situation does not lend itself to

analysis purely in terms of a set of supply areas or a set of market areas.

How, then, can we most effectively analyze such a pattern?

Except in

the unlikely situation in which the patterns of supply and demand coincide

(which would mean that no transfer is required and that each point is

self-sufficient in this particular product), there will be surplus areas where

local output exceeds local consumption, and deficit areas where the opposite

situation prevails. The product will be transferred from surplus areas to

deficit areas; and in order to motivate the flow, there must be a price

differential corresponding to the costs of transfer along the paths of

flow.

The

relationship between price patterns and transfer can be demonstrated as

follows. Suppose we were to map the spatial variations in the price of the

good, depicting a price surface by plotting a set of contour lines, each

connecting points at which the price is at some particular level. The iso

price lines (isotims) corresponding to the highest prices would occur in

the principal deficit areas, and those corresponding to the lowest prices would

occur in the principal surplus areas. The price gradient along any path would

be determined by the frequency with which we cross successive isoprice contours

as we traverse that path. Shipments of the commodity would be most likely to

occur along the paths with the steepest price gradients, and such paths would

cross the isoprice lines at right angles. Actual shipments would occur wherever

there is a price gradient at least as steep as the gradient of transfer costs;

and in an equilibrium situation, we should expect that these shipments would

result in no price gradient being substantially steeper than the transfer cost

gradient.

Such a

graphic analysis does not, however, explicitly recognize the relation between

supply and demand patterns that creates the price differentials giving rise to

shipments. William Warntz has suggested an empirically feasible shortcut method

of measuring this supply-demand relation that utilizes the access potential

index described later.16

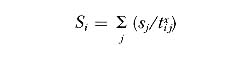

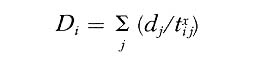

For any

given point i, we can construct an index of local and nearby supply, or

"access to supply," by the following formula:

where sj is the output at any supply location j,

tij, is the transfer cost from that supply location j to the given point i, and x is an exponent empirically

chosen to provide the best fit to the observed statistics. For the same point i, we can construct also an index of local and nearby demand, or access

to market, by the analogous formula:

With both

indices derived for each location, we can identify surplus areas as those where

the supply index is greater than the demand index, and deficit areas as those

for which the demand index is greater than the supply index. We should expect

that spatial variations of the price of the good should be positively

correlated with the demand index and negatively correlated with the supply

index; this expectation was borne out in some of Warntz’s studies of the

price patterns of agricultural commodities.

5.6 SUMMARY

Just as

some activities are characterized by mutual repulsion among units, others are

characterized by cohesive or clustering (agglomerative) forces. These forces

may result from demand or production (supply) characteristics of the activity

in question.

In some

instances, each unit finds advantage in locating near others of the same kind

primarily because the units are not exactly identical. This generally happens

when the output is varied and changing somewhat unpredictably, so that buyers

need to "shop"—that is, to compare various sellers’ offerings.

Selling locations attract buyers according to how wide a choice they can offer;

therefore, sellers gain by being part of a large cluster.

Further

agglomerative forces arise from the external economies of a cluster large

enough to support a variety of highly specialized suppliers of inputs: labor,

components, services, and so forth. These clusters also are characteristic of

activities dealing with nonstandardized and perishable outputs and inputs. In

such activities the units are small and generally only one to a firm.

Lichtenberg’s classic study of external-economy industries showed the

nature of such clustering and its importance in the economy of a large

metropolis such as New York.

As the size

of an urban area increases, it becomes capable of supporting activities and

services that are external to any cluster but that generate economies for a

number of clusters. Urbanization economies of this sort imply important

advantages for activities located in large metropolitan areas, where we observe

complexes of interacting activities.

Although a

contrast has been drawn between activities dominated by mutual repulsion of

units and those dominated by mutual attraction (agglomeration), there are some

elements of both mutual repulsion and attraction in many activities. There are

also many situations in which sellers have market areas, and buyers at the same

time have supply areas.

TECHNICAL TERMS INTRODUCED IN THIS

CHAPTER

|

External economies of

agglomeration |

Urbanization

economies |

|

Unit

economies |

Price

surface |

|

Firm

economies |

Isoprice line, or

isotim |

|

Cluster

economies |

|

SELECTED READINGS

Brian J. L.

Berry, Geography of Market Centers and Retail Distribution (Englewood

Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall, 1967).

Stan

Czamanski and Luiz Augusto de Q. Ablas, "Identification of Industrial Clusters

and Complexes: A Comparison of Methods and Findings," Urban Studies, 16,

1 (February 1979), 61-80.

Robert M.

Lichtenberg, One-Tenth of a Nation (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University

Press, 1958).

Hugh 0. Nourse, Regional

Economics (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1968), pp. 85-92.

Harry W. Richardson, Urban Economics (Hinsdale, Ill.: Dryden Press, 1978), Chapter

3.

David Segal, Urban

Economics (Homewood, Ill.: Richard D. Irwin, 1977), Chapter 4.

ENDNOTES

1. B. Curtis Eaton and Richard G. Lipsey. "Comparison Shopping and

the Clustering of Homogeneous Firms," Journal of Regional Science, 19, 4

(November 1979), 421-435, examine some locational implications of comparison

shopping in a more theoretical context.

2. In Section 5.4 we shall distinguish yet another

level at which economies of size may appear; there, we shall find that such

economies are also associated with urbanization per se.

3. What are here identified as "cluster" economies are sometimes

referred to as economies of localization. Alfred Marshall’s succinct

characterization of the ‘economies of localized industries" is often

quoted from his Principles of Economics, 8th ed. (London: Macmillan,

1925), Book IV, Chapter 10. F. S. Hall’s Census monograph, "The

Localization of Industries" (U.S. Census of 1900, Manufactures, Part 1,

pp. cxc—ccxiv), reported on the development of highly clustered patterns

of individual manufacturing industries toward the end of the nineteenth

century. Unfortunately, however, the term "localization" has also been used

synonymously with "location" and even in the sense of "dispersion," so it is

best avoided.

4. A thorough and original discussion of business organization and

location in terms of these several optima appears in E. A. G. Robinson, The

Structure of Competitive Industry, rev. ed. (Chicago: University of Chicago

Press, 1958).

5. Robert M. Lichtenberg, One-Tenth of a Nation (Cambridge,

Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1960). Lichtenberg’s list of

"external-economy industries" includes five more, in which the region’s

share was less than 10.4 percent: industrial patterns and molds, separate

trousers, men’s dress shirts and nightwear, woolen and worsted fabrics,

and special dies, tools, and metal-working machinery attachments. He does not

explicitly categorize any nonmanufacturing activities as

external-economy-oriented though he does discuss the heavy concentration of

central offices of large industrial corporations in the New York metropolitan

region Among the 500 largest such corporations as listed by Fortune magazine in 1959, 155 (31 percent) maintained their headquarters in the

region. The region’s share was greater still for the largest corporations,

rising to 44.2 percent of those with $750 million or more in assets (ibid., Chapter 5 and specifically Table .37, p. 155).

6. Lichtenberg gives a full listing of industries by locational

category in ibid., Appendix B.

7. For an empirical analysis of cluster tendencies involving related

lines of retail trade, see Arthur Getis and Judith M. Getis, "Retail Store

Spatial Affinities," Urban Studies, 5, 3 (November 1968), 317-322. For a

sophisticated and challenging empirical analysis of which activities cluster

with which, see Joel Bergsman, Peter Greenston, and Robert Healy, "The

Agglomeration Process in Urban Growth," Urban Studies,9, 3 (October

1972), 263-288; and for a survey of related literature, see Stan Czamanski and

Luiz Augusto de Q. Ablas, "Identification of Industrial Clusters and Complexes:

A Comparison of Methods and Findings," Urban Studies, 16, 1 (February

1979), 61-80.

8.

Hall’s 1900 Census monograph, previously cited, gives numerous further

examples.

9. Economic historians have often noted the important role of the

influx of Germans to the United States in the mid-nineteenth century in

establishing concentrations of certain industries in which they had special

skills, such as optical and other scientific instruments in Rochester, brewing

in Milwaukee and St. Louis, and tanning and shoemaking in these and other

Midwestern cities.

10. A second approach to this measurement problem

entails the direct estimation of the returns to scale exhibited by activities

in metropolitan areas. Gerald A. Carlino, "Increasing Returns to Scale in

Metropolitan Manufacturing," Journal of Regional Science, 19, 3 (August

1979), 363-373, provides estimates of this sort and attempts to decompose them

into economies related to the size of the unit, cluster, or urban area

associated with a given activity.

11. The assumption that the same wage rate prevails in

both cities implies that this productivity difference reflects a long-run

equilibrium in which spatial factor price differentials have been eliminated.

In fact, the labor supply curve may be positively inclined, indicating that

higher wages must be paid to attract more workers. Indeed, it may even be

necessary to pay workers higher wages in order to compensate for the

"disamenities" of urban life. (On this point see Oded Izraeli, "Externalities

and Intercity Wage and Price Differentials," in George S. Tolley, Philip E.

Graves, and John L. Gardner (eds.), Urban Growth Policy in a Market Economy [New York: Academic Press, 1979], pp. 159-194.) Recognition of these labor

supply conditions would imply that adjustments to the measure of productivity

gain described above are required in order to "net-out" these effects and

identify "real" productivity gains. The reader interested in these issues

should see Michael S. Fogarty and Gasper Garofalo, "An Exploration of the Real

Productivity Effects of Cities," Review of Regional Studies, 8,1 (Spring

1978), 65-82; and Fogarty and Garofalo, "Urban Size and the Amenity Structure

of Cities," Journal of Urban Economics, 8,3 (November 1980), 350-361.

Fogarty and Garofalo use the graphical analysis presented here to develop

perspective on their related work and explore the concept of "real

productivity" in some depth.

12. See David Segal, "Are There Returns to Scale in City

Size?" Review of Economics and Statistics, 58, 3 (August 1976), 339-350;

and Leo A. Sveikauskas, "The Productivity of Cities," Quarterly Journal of

Economics, 89, 3 (August 1975), 392-413. For qualifications and extensions

of the method and results presented by these authors, see the articles by

Fogarty and Garofalo cited in the preceding footnote and Ronald L. Moomaw,

"Productivity and City Size: A Critique of the Evidence," Quarterly Journal

of Economics, 94, 4 (November 1981), 675-688.

13. Actually, Segal accounts for differences in labor

quality among cities by setting b = kßkqikwhere qik reflects the city’s labor force composition

by education, sex, race, and age. He also includes a vector of site

characteristics (accounting for climate, natural resources, etc.) in the

multiplicative constant.

kßkqikwhere qik reflects the city’s labor force composition

by education, sex, race, and age. He also includes a vector of site

characteristics (accounting for climate, natural resources, etc.) in the

multiplicative constant.

14. In Chapter 8, we

shall find that the growth rate of nonmetropolitan areas has exceeded that of

metropolitan areas in recent years. Some researchers have speculated that this

also may be due to the changing structure of agglomeration

economies.

15. If there are many sellers of a standardized

commodity at one location, so that they are in nearly perfect competition, any

seller could dispose of its entire output while confining its sales to that

part of the market providing the largest profit margin. Consequently, any

attempt to establish a discriminatory pricing system would break down.

16. William Warntz, Toward a Geography of Price (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1959).