|

10.1 INTRODUCTION

The

importance of manpower supply as a location factor is suggested by the sheer

magnitude of labor costs as an element in the total outlays of productive

enterprises. In the United States, wage and salary payments, and supplements

thereto, account for about three-fourths of the national income, and this does

not include the earnings of self-employed people and business proprietors (for

example, farmers, store owners, and free-lance professionals), which mainly

represent a return to their labor. Accordingly, we should expect to find many

kinds of activities locationally sensitive to the differentials in the

availability, price, and quality of labor.

Labor’s role as a purchased input, however, is only one aspect

of the locational interdependence of people and their economic activities.

People in their role as consumers of the final output of goods and services

affect the locational choices of market-oriented activities. They play still

another role as users of residential land; and in urban areas, residence is by

far the largest land use. Finally, and most important, the purpose of the whole

economic system is to provide a livelihood for people. Regional economics is

vitally concerned with regional income differences, the opportunities found in

different types of communities, and regional population growth and

migration.

The present

chapter is devoted to integrating and exploring these various aspects of "the

location of people." We begin by considering the locational differences in the

rewards or "price" of labor.

10.2 A LOOK AT SOME DIFFERENTIALS

Comparing

wages or incomes among different areas is not as straightforward a matter as it

might appear, even when appropriate data are at hand. It is a question of what

comparison is relevant to the question we have in mind. For example, if we want

to gauge the relative opulence of two communities (perhaps as an indication of

how rich a market each would provide for consumer goods and services), then

average personal income in dollars per family or per person would be

appropriate to compare. But an individual looking for an area where his work

will be well rewarded would do better to compare real earnings in his or

her occupational category; that is, monetary earnings deflated by a

cost-of-living index. Finally, an employer looking for a good labor supply

location would be most interested in comparisons of labor cost, based on

monetary wage-and-salary rates adjusted for labor productivity and fringe

benefits. The relevance of such different measures should be kept in mind as we

look at the data.

10.2.1

Differentials in Pay Levels

Rates of

pay in any specific occupation can differ widely from one place to another and

even within the same labor market area. For example, in 1978 the union hourly

wage scale for laborers and helpers in the building trades averaged $8.54 for

65 cities surveyed by the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, with the rate in

individual cities ranging from a high of $10.54 in Cleveland, Ohio, to a low of

$5.21 in Huntsville, Alabama.1

The

differentials among regions are not entirely erratic. Some evidence of an

underlying pattern appears in Table 10-1, in which the labor markets are

classified by broad region and by size. In each of the three broad occupational

categories, the South shows up as the region with the lowest pay levels. The

West and North Central regions pay generally higher rates. In addition, with

the exception of two occupational categories in the North Central region, there

is a tendency for rates to be higher in the larger metropolitan areas. Finally,

it can be noted that the interregional disparities are wider for unskilled

workers than for the other groups. This feature of the pattern will be

explained later.

Although

the figures cited are based on careful comparisons of the standard earnings

rate in (as nearly as possible) identical jobs, they do not give a complete

picture of relative advantages for either the employee or the employer. No

account is taken of the increasingly important fringe benefits (vacations,

overtime pay, sick leave, pensions, and so on) or of differences in the cost of

living. Nor do these comparisons give us any indication of differentials in the

productivity of workers, which also play a part in determining the

employer’s labor cost per unit of output.

10.2.2

Income Differentials

Income

differentials also show a discernible pattern according to region and size of

urban place. But the difference in per capita or per family incomes between two

areas is, of course, determined not only by relative earnings levels in

specific occupations but also by differences in the occupational and industry

mix of the areas, the degree of labor force participation, and unemployment

rates. For example, regional per capita personal income in 1981 varied as shown

in Table 10-2.

The

relation of income level to type of urban or rural place of residence is shown

in Table 10-3. We observe there that in 1980, incomes were higher in

metropolitan areas than in nonmetropolitan areas; higher in larger metropolitan

areas than in smaller metropolitan areas; higher outside central cities than

inside of central cities; and higher in nonfarm rural areas than on

farms.

10.2.3 Differentials in Living Costs and Real

Income

From the

standpoint of the worker, the possible advantage of working in a high-wage or

high-income area depends partly on how expensive it is to live there. Most of

us are aware that there are considerable differences in the cost of living in

different parts of the country and different sizes of community.

Although it

is impossible to measure relative living costs comprehensively so as to take

into account all the needs and preferences of an individual, a useful

indication is provided by surveys of the comparative cost, in different

locations, of securing a specific "standard family budget" of goods and

services. Table 10-4 summarizes the findings of a

survey of this type. A fairly distinct pattern of differentials appears. With

few exceptions, living costs are higher in metropolitan areas than in

nonmetropolitan areas for major kinds of expenditure. When one looks at total

family consumption, living costs in the South are clearly lower than elsewhere

in both metropolitan and nonmetropolitan areas. This is attributable to the

comparatively low cost of housing and food in the South. Also, examination of

the indices for individual SMSAs reported in the survey suggests that high

housing costs are associated with large city size, rapid recent growth, and

rigorous climate.

A study of

SMSA characteristics associated with living cost for low-, moderate-, and

high-income families in 38 SMSAs, using regression analysis, found that 64

percent of the total variance in living costs for moderate- and high-income

families could be explained in terms of three significant variables:

population, location in the Southeast or elsewhere, and the degree to which

spatial expansion of the urban area was subject to "topological and physical

constraints" (for example, water or mountain barriers) on its periphery. This

last factor could be expected to influence travel distances and costs and also

land cost. Climate did not show up as a significantly correlated

characteristic, nor did size of place in the case of low-income

families.2

A crude

picture of differentials in real incomes among metropolitan areas can be

obtained by dividing the per capita personal income for each area by the index

of consumer budget costs for the same area.3For

the sample of metropolitan areas on which Table 10-4 is based, the real income

index so obtained is rather well correlated with per capita personal money

income, while per capita personal money income is somewhat less strongly

correlated with the index of consumer budget costs.

Thus living

costs tend to be high where money incomes are high (not surprisingly, in view

of the important impact of service costs and other local labor costs on the

consumer budget). But the interarea differentials seem to be wider for money

incomes than for budget costs; so real income thus estimated is a little higher

in places where money income is high. By the same token, interarea

differentials in real income are much smaller than those in money

income.

There is

evidence that similar relationships prevail also when we compare different size

classes of places,4though it is impossible to

compare adequately the psychic satisfactions and costs that come from living in

large cities as against smaller places.

10.3 THE SUPPLY OF LABOR AT A LOCATION

In trying

to understand the causes and effects of wage and income differentials, it is

useful to consider separately the supply and demand sides of the local labor

market. The aggregate supply of labor in a community may be quite inelastic in

the short run, since it can change only through migration or changes in labor

force participation. For a single activity or occupation within the labor

market area, the supply is more elastic because it can be affected by workers

changing their activities or occupations as well as by migration and changes in

the labor force. The labor supply as seen by an individual employer is still

more elastic, and for small employers in a large labor market almost perfectly

so.

10.3.1

Work Location Preferences and Labor Mobility

There are

many reasons for preferring a job in one area to the same kind of job in

another area, and the decision to move can be very complex. A systematic

evaluation of costs and benefits is in order, much as a decision-maker in

business evaluates the pros and cons of an investment. Thus the potential

migrant would want to recognize what he or she would be giving up (the

opportunity costs of the move) and make a good guess about what would lie in

store in the new location.

Neither of

these tasks is particularly easy, and a number of considerations would have to

be recognized. First, it is not adequate to compare only basic wages; all

fringe benefits must be considered as well. Also, for an increasingly large

share of the work force, the employment prospects of the spouse may be as

important as that of the "primary" wage earner.5 Second, a community with cheaper living costs might be preferred in the absence

of any pay differential. Third, various aspects of the quality of the job, such

as security and prospects of advancement, may be considered. Expected growth in

earnings some years down the road may be an important factor in the decision to

act now.6 Finally, other aspects of the

desirability of the community as a place to live can include, for example,

climate, cultural and social opportunities, and access to other places that one

might like to visit.7 Differences among places on

any of these accounts can be compared to money income differentials: How much

additional compensation is required to give up immediate access to cultural

events, or how much less would one be willing to accept in terms of earnings

for a climate that suits one’s tastes?

Spatial

mobility refers to people’s propensity to change locations in response

to some measurable set of incentives, identified in practice as "real income"

or simply as money wage rates deflated by a cost-of-living index. If mobility

in this sense were perfect and real wages thus equal everywhere, there would be

differentials in money wages paralleling the differentials in living costs. A

labor market where the living costs were 10 percent above average would pay

wages 10 percent above average, but real wages there would be the same as

anywhere else.

The term equalizing differentials has been applied to this kind of money wage or

income differential.8The pattern of actual money

differentials is, then, made up of two components: (1) equalizing

differentials, which would exist even in the absence of any impediment to labor

mobility, and (2) real differentials, representing differences in real

income and thus presumably caused by impediments to mobility.

The

significance of this distinction is that workers can logically be

expected to choose locations and to move in response to real differentials; whereas employers looking for cheap labor will be

more interested in the total money wage differential, which combines

both real and equalizing differentials.

These

concepts of real and money wages, cost of living, equalizing and real

differentials, and mobility help us to understand some basic motivations of the

locational choices of employees and employers; but unfortunately they are not

very sharp tools. We have already noted the impossibility of including in

indices of income and living costs all the considerations affecting the

desirability of a place to live. For example, such indices take no account of

the attractions of a mild and sunny climate (except as reflected in housing

costs), the dirt and discomforts of life in a large industrial city, the social

pressures and cultural voids of a small town, or the advantage to a research

worker of being stationed where the action is in his or her field. As a result

of our inability to measure real income fully, we are also unable to measure

mobility in a completely unambiguous way. If a family, for example, likes the

physical and social climate of its surroundings and refrains from moving to

another area where the pay is higher both in money terms and as deflated by a

conventional family budget cost index, should we ascribe its failure to move to

a lack of mobility?

A further

difficulty with the simple concept of real and equalizing differentials is the

implication that migration is not merely motivated by real-income differentials

but tends to eliminate them. Under certain conditions it is possible for

migration, even when so motivated, to leave the differential unchanged or even

to widen it. We need to look further into both the causes and the consequences

of migration.

10.3.2

Who Migrates: Why, When, and Where?

Migration

is influenced by three conditions: the characteristics of both the origin and

destination areas, the difficulties of the journey itself, and the

characteristics of the migrant.

Reasons for Moving.It is a drastic oversimplification

to explain migration simply on the basis of response to differentials in wage

rates, income, or employment opportunity. The U.S. Bureau of the Census bases

its tabulations of migration on changes in residence. Since some of these are

local (moves within the same county) and others involve substantial distance

(intercounty moves), one would expect reasons for moving to differ

widely.

Those

persons who move only within the same county are predominantly influenced by

housing considerations. Since all of a county is generally regarded as being

included within a single labor market or commuting range, job changes are

related only to a minor extent with intracounty moves. Most such movers are not

changing jobs.

For those

who move to a different county the picture is quite different, with employment

changes (including entry to or exit from military service) emerging as the

major reasons for migrating. This reflects the fact that an intercounty

migration generally involves shifting to a different labor market beyond the

commuting range for the former job. A change of residence is involved but is

not the primary motivation.

Characteristics of Origin and Destination Areas. The

characteristics most obviously affecting attractiveness to the individual

migrant have already been suggested. In addition, we should expect that a

larger place would have more migrants arriving and departing than a smaller

place, more or less in proportion to size. But size itself can significantly

affect the appeal of a place for the individual. Historically, migrants have

responded to the greater variety of job opportunities in larger urban places

and their suburbs by migrating to them in numbers somewhat more than

proportional to their size.

Rather than

thinking of migration as being motivated simply by net advantages of some

places over others, it is useful to separate the pull of attractive

characteristics from the push of unattractive ones. Clearly, many people

migrate because they do not like it where they are, or perhaps are even being

forced out by economic, political, or social pressures. The basic decision is

to get out, and the choice of a particular place to migrate to is a secondary

and subsequent decision, involving a somewhat different set of considerations.

On the other hand, some areas can be so generally attractive as to pull

migrants from a wide variety of other locations, including many who were

reasonably well satisfied where they were.9

Recent

studies on migration using detailed data on flows in both directions (rather

than just net flows) have considerably revised earlier notions of push and

pull. Rather surprisingly, it appears that in most cases the so-called push

factor explaining out-migration from an area is not primarily the economic

characteristics of the area (such as low wages or high unemployment) but the

demographic characteristics of the population of the area. Areas with a high

proportion of well-educated young adults have high rates of out-migration,

regardless of local economic opportunity. The pull factor (that is, the

migrant’s choice of where to go) is, however, primarily a matter of the

economic characteristics of areas. Migration is consistently heavier into

prosperous areas. Accordingly, the observed net migration losses of depressed

areas generally reflect low in-migration but not high out-migration, and the

net migration gains of prosperous areas reflect high in-migration rather than

low out-migration.10

Difficulties of the Journey. Within a country, distance

is perhaps the most obviously significant characteristic of the migration

journey, and virtually all analyses of migration flows have evaluated the

extent to which migration streams attenuate with longer distance. Thus a simple

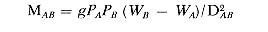

"gravity model" of migration posits that the annual net migration from A to B will be proportional to the populations of A and B and to the size of some differential (say, in wage rates) between A and B, and inversely proportional to the square of the distance from A to B, as follows:

(where the

Ps represent populations, the Ws wage rates, D the distance, M the number of migrants per unit of time, and g a constant with a

value depending on what units are used for the variables).11 This basic migration flow model has been statistically

tested and modified in many ways in the attempt to make it more realistic. It

has already been suggested that in many circumstances at least, there is a

"scale effect" upon migration, which can be incorporated in the model by giving

the populations an exponent greater than 1. Any relevant factor of differential

advantage that can be quantified (for example, unemployment rates, mean summer

or winter temperature, percentage of sunny days, average education or income

level of the population, percentage of housing in good condition, crime rates,

insurance rates, or air pollution) can be introduced, with whatever relative

weighting the user of the model deems appropriate.

The

distance factor in the model likewise can be assigned a different exponent to

fit the circumstances (there is nothing special about the square of the

distance, except for the law of physical gravitation) and elaborated in

various ways. Actually, distance per se is at best only loosely related to the

difficulties attending migration. The factors involved are actual moving costs

(which can sometimes be the least important obstacle), uncertainty, risk and

investment of time involved (including that associated with acquiring

information), restrictions on migration per Se, and what is sometimes called social distance—suggesting the degree of difficulty the migrant may

have in making adequate social adjustment after he or she arrives.12 As an example of this last factor, a model designed by

W. H. Somermeijer to explain Dutch internal migration flows included a term

that measured the difference in the Catholic-Protestant ratio between the two

areas. Introduction of this term substantially improved the model’s

explanatory power, suggesting that members of each religious persuasion tend to

move mainly to areas where their coreligionists predominate. 13

Social

distance depends partly, of course, on the individual migrant. But wide social

distances between communities and regions (that is, great heterogeneity) tend

to restrict migration flows to those individuals who can most easily make the

required adjustment. With the improvement in communications and travel, social

distance in space tends to lessen; but it is still a factor, for example,

between French and English Canada, between the North and the Deep South in the

United States, or between farm and city.14

Another

feature of migration paths is that they seem to be subject to economies of

volume of traffic along any one route. Well-beaten paths become increasingly

easy and popular for successive migrants. This is so for a variety of reasons.

Sometimes (as in the case of earlier transoceanic and more recent Puerto

Rico-to-mainland migrant travel) transport agencies have given special rates or

in other ways have favored the increase of migrant travel on the most

frequented routes. Perhaps more generally applicable and more important is the

fact that migrants try to minimize uncertainties and risks by choosing places

about which they have at least a little information and where they will find

relatives, friends, or others from their home areas who will help them to gain

a foothold.15 This tendency is particularly

important, of course, when the social distance is large. It goes far to explain

the heavy concentration of late-nineteenth-century European migrants to the

United States in a few large cities, and the even more remarkable concentration

of particular ethnic and sub-ethnic groups in certain cities and neighborhoods,

which even now retain unto the third generation some of their special

character. The most recent ethnically distinctive waves of migration to

American cities—those of blacks, Puerto Ricans, and Chicanos—have in

the same fashion followed a few well-beaten paths. For example, it has been

established that Southern black migrants to Chicago came mainly from certain

sections of the South, while those going to Washington, D.C., or Baltimore

originated in other Southern areas, and those going to the West Coast in still

other areas. Recent migrants from the Caribbean (other than those from Puerto

Rico) remain highly concentrated in the Miami area.

An analysis

of labor mobility in the United States between 1957 and 1960, based on Social

Security records, gives striking evidence of the beaten-path effect where migration of blacks is concerned. For white workers, both male and

female, migration flows were significantly related to earnings differentials

(positively) and to distance (negatively) as we might expect. For black men,

however (and to a lesser extent for black women), earnings differentials and

distance appeared to be less important determinants than either the number of

blacks or the proportion of blacks in the work force of the destination area.

In other words, blacks (or at any rate, black males) were selectively attracted

to labor markets in which there already was a high proportion of blacks.16

The

tendency of migration to channelize in well-beaten paths provides part of the

explanation for another characteristic of migration streams already mentioned;

namely, that places with high rates of inward migration tend to have high rates

of outward migration as well. This so-called counterstream effect was

noted as long ago as the 1880s in E. G. Ravenstein’s pioneer statement of

migration principles, and has been amply verified since.17

The point

here is that a well-beaten path eases travel in both directions.

Migrants generally come to a place with incomplete knowledge, and many of the

disappointed ones simply retrace their steps. Also, a city that offers

especially favorable adjustment opportunities for migrants is likely to serve

as a "port of entry" for migrants coming into that region or country. New York

has historically been the entry place for transatlantic immigrants, and Chicago

has functioned as an important first destination for Mexicans migrating to the

American Midwest. In such cases, many of the migrants move out again (either to

other places in the region or perhaps back to their place of origin), so the

out-migration rate of such an entry point or staging area is likely to be high.

More generally, it is plausible to assume that people who have just migrated

are especially mobile by circumstances or taste and hence more likely than

others to swell the outward flow.

Migration

flows over long distances within the same country have historically involved a

considerable amount of what is sometimes called chain migration. Most of

the migrants move relatively short distances, but the moves are predominantly

in one direction, forming a stream. As people move from B to A, they are replaced in B by migrants from C, who in turn are

replaced by migrants from D. It has been established that most of the

massive redistribution of population in England during the Industrial

Revolution was carried out in such fashion by short-distance moves cumulating

toward the new industrial towns.18

Characteristics of the Migrant. Migration is basically selective. Some people are far more prone to migrate than are others.

This is often expressed as a difference in the mobility of different groups,

but we really cannot explain all of the difference in that way, since the incentives to migrate are not the same. For example, a young scientist

fresh out of school is confronted with a quite different set of pushes and

pulls than an aging farmer, an established business executive, a manual

laborer, or a wealthy widow.

The most

conspicuous differences in migration rates are those experienced by the

individual in passing through successive stages of a lifetime. These changes

are (as shown in Figure 10-1) rather similar for the

two sexes; for simplicity’s sake we describe them here in male

terms.

A very

young child is relatively portable. After he enters school and has older, more

settled parents and probably more brothers or sisters, his probability of

moving declines. The rate rises suddenly when he is ready to look for a job or

choose a college, and it remains high until after he is married and has

children of his own. As his stake in his job and community grows, and as his

and his family’s other local ties develop, he becomes less and less likely

to move. His mobility recovers somewhat at the stage when all of his children

are on their own, and again at the customary mid-sixties retirement age. After

about age seventy, migration rates tend to rise a little, presumably reflecting

adjustments to death of the spouse or to growing incapacity.

These

characteristic life-cycle variations are manifest in Figure 10-1, showing United States migration rates by

age and sex. The pattern is blurred in the aggregate, of course, by the fact

that not all people enter the labor force, marry, or retire at the same ages.

But age remains the characteristic most distinctly associated with

migration-rate differentials. Most of the migration that occurs (except in

massive displacements of populations by military or political force or by

natural disaster) is done by people in young adult age groups.

Certain

other individual characteristics also substantially affect migration rates. The

most important are marital status, parenthood, and level of education. Table

10-5 shows migration rates over a five-year interval for men in three mature

age groups (that is, after their schooling was probably completed), according

to amount of schooling. We see that higher education is associated with higher

migration rates. Occupational status also has a bearing on migration rates. For

a given age category, individuals with higher occupational status have greater

mobility.19

In addition

to such regularly recorded characteristics as we have considered, individuals

have many other personal characteristics that influence their propensity to

migrate. Some people are simply more footloose, more adventurous, more easily

dissatisfied, or more ambitious than others, or in countless other ways more

mobile.

These wide

differences in migration rates among different kinds of people mean, of course,

that those who migrate are almost never a representative cross section of the

population of either their area of origin or their area of destination. A

migration stream substantially alters the make-up of the population and the

labor force in both areas.

The selectivity of migration is greatest when the journey is difficult, when

the areas of origin and destination are in sharp contrast, and when the

population itself is highly diverse in such characteristics as education,

income level, occupational experience, and ethnic or racial background.

Migrants generally seem to be somewhat above the average of the origin area in terms of energy, ability, and training; this suggests that the

direct effect on the remaining population is to lower its average "quality."

One of the oldest clichés regarding emigration, in fact, is that it

tends to drain the best people out of an area, thus damaging the prospects for

industrialization or other economic development.

An

intensive study of the occupational status of American men aged twenty to

sixty-four came to these conclusions:

Migration has

become increasingly selective of high potential achievers in recent

decades.

…The careers of migrants

are in almost all comparisons, clearly superior to those of nonmigrants. . . .

Whether migration between regions or between communities is examined; whether

migrants are compared to nonmigrants within ethnic-nativity groupings or

without employing these controls; whether education and first job are held

constant; and whether migrants are compared to natives in their place of origin

or their place of destination— migrants tend to attain higher occupational

levels and to experience more upward mobility than nonmigrants, with Only a few

exceptions.

…Migrants from urban

places, though not those from rural areas, enjoy higher status than the natives

in the community to which they have come, regardless of its size.20

These

findings go well beyond the traditional folklore about selective migration in

that they suggest (1) that migrants (except from rural areas) tend to be

superior to the population of the destination area as well as of the

origin area, and (2) that selectivity may be increasing, contrary to the

expectation that more general literacy and other trends enhance the mobility of

an increasing proportion of the population.

Another

study, relating to migrants to the industrial metropolis of Monterrey, Mexico,

between 1940 and 196021 gives a rather different

picture. Migration appears to have become much less selective with respect to

populations of origin in that interval. Early in the period, only a few of the

more highly educated ventured the move to the city; later, mobility increased,

so that villagers of all educational and income levels became more nearly

representative of the populations of its areas of origin, while at the

same time it was becoming increasingly different from (educationally inferior

to) the population of the urban destination area.22

Migration

selectivity, then, can depend to a large extent on the state of development of

the regions involved and can change in character fairly rapidly. It has already

been suggested that a broadening of education and economic opportunity in

less-developed regions can reduce selectivity. Finally, Everett Lee has

proposed a plausible but not easily verifiable hypothesis: that migration

motivated by pull tends to be positively selective (i.e., the more

productive people are the ones who go), whereas migration motivated by push

tends to be negatively selective.

Factors at origin

operate most stringently against persons who in some way have failed

economically or socially. Though there are conditions in many places which push

out the unorthodox and the highly creative, it is more likely to be the

uneducated or the disturbed who are forced to migrate.23

Inward, Outward, and Net Migration: Three Hypotheses. The typical age selectivity of migration is sometimes an important factor

accounting for the observed tendency that places with high in-migration rates

have high out-migration rates as well. The most mobile age groups (and perhaps

also the individuals most mobile by temperament or other characteristics) are

present in abnormally high proportion in a fast-growing area with high recent

and current in-migration; and such local demographic characteristics play a

large part in determining how many people leave an area.24

We have

learned that the relationships among inward, outward, and net migration are

more complex than one might suspect. Let us review them in terms of three

hypotheses or "laws of migration," using Figure 10-2 as a graphic aid.

The naive

or common-sense" expectation regarding migration into and out of an area is

that if the area is attractive as a place to work and live, there will be a net

inward flow reflecting large inward and small outward migration; while if the

area is unattractive, there will be a net outflow reflecting large outward and

small inward migration. This hypothesis is represented diagrammatically in the

first panel, (a), of Figure 10-2, where the

dots could represent different labor market areas or the same area at different

times. In-migration and out-migration rates are measured on the horizontal and

vertical axes respectively. The 45-degree line represents zero net migration.

The various areas show a pattern of negative correlation of out-migration, with

both inward and net migration: "Attractive" areas are those in the lower right

part of the scatter, and "unattractive" areas are those above and to the left

of the diagonal.

The second

panel, (b), depicts the contrasting relationship, previously suggested

on the basis of migration selectivity and other factors, which we might

designate as the Lowry hypothesis. Here the rate of out-migration is positively correlated with both inward and net migration.

Still

another view is that shown in the third panel, (c), which we may call

the Beale hypothesis.25 Using 1955-1960 data for

509 State Economic Areas demarcated by the Census Bureau,26Beale discovered a relationship schematically

resembling that of Figure 10-2 (c). He found

that high gross out-migration can be associated with either high net

in-migration or high net out-migration. The net rate is mainly determined by

out-migration when the net is negative, and by in-migration when the net is

positive. We may interpret this as meaning that the "Lowry effect" dominates in

relatively prosperous and growing areas; whereas in areas that are seriously

depressed the predominant effect is the "common-sense" one: Poor prospects both

discourage inflow and encourage outflow, and economic factors exert both pull

and push.

The

significance of this issue is far from trivial, as Beale points out and as we

shall more fully appreciate in the context of Chapters 11 and 12. If migration out of seriously depressed or

backward areas is assumed to be affected only by demographic characteristics of

the population and not by the level of unemployment or income, then measures to

stimulate activity in such areas would not reduce out-migration (in fact,

according to the Lowry hypothesis they would eventually increase it). The Beale

findings suggest, however, that such stimulus may, in some cases at least,

retard out-migration. In choosing among policy decisions regarding aid to

depressed or backward areas, it is of some importance to try to gauge this

possible impact.

Changes in Migration Rates. There are a number of

reasons why one might expect migration rates to increase over time. Lee has

suggested that increasing diversity of the opportunities afforded by different

areas, increasingly diverse specialization of people’s capabilities and

preferences, the beaten-path effect, and the increasingly wide knowledge and

experience of other locations that is brought about by education, better

communication, more income, and increased leisure to travel would each enhance

the mobility of the population.

Changes in

the socioeconomic and demographic characteristics of households have been

working in the opposite direction, however. For short-distance (intracounty)

moves, decreases in average size of household and increases in home ownership

are associated with decreases in mobility. With respect to long-distance moves,

the rising incidence of two-wage-earner households also discourages

mobility.

Recent

tabulations of migration data gathered on an annual basis from sample surveys

since 1948 show that the net effect of these countervailing forces has been a

consistent decline in the overall migration rate. For example, the average

annual rate for the twelve-month period March to March has fallen from 20.6 in

1961-1962 to 18.7 in 1970-1971 and to 17.2 in 1980-1981. Thus in the 1960-1961

period, roughly 21 percent of the population changed residences in the United

States, whereas that number had fallen to about 17 percent in the 1980-1981

period.27

Much of

this trend can be attributed to decreases in the frequency of intracounty

moves. However, there are also indications that regions have become more alike,

so that in some respects the incentives for long-distance moves have

probably lessened. Regional incomes in any case have tended to converge toward

the national average. Thus in addition to the socioeconomic and demographic

factors mentioned above, reduced migration incentives could also have offset

increases in personal mobility.

Migration

rates show marked seasonal and cyclical variations. In general, prosperity

favors migration because opportunities are more plentiful, risks of

unemployment at the new location are less, and migrants themselves are in a

better financial position. In periods of economic recession or depression,

people tend to look for the place with the best economic security. This may

mean staying where they are or (in the case of fairly recent migrants)

returning to their last place of residence. Thus the long-term migration stream

toward places with better long-term prospects is temporarily interrupted or

even reversed by severe recessions. For example, in the worst years of the

Great Depression of the 1930s, the longstanding net flows of migrants from farm

to nonfarm areas and from foreign countries to the United States were both

temporarily reversed.

The Effectiveness of

Migration. When people migrate, they are seeking to better their

prospects. How well does migration accomplish that purpose, and how does it

affect people other than those who migrate?

The answer obviously

depends in part on how accurately people size up the prospects when they decide

to move (or not to). The better informed they are, the greater the probability

that migration will justify itself and will contribute to a more efficient

allocation of human resources in the economy as a whole. Thus public policy

with regard to migration should, first, help potential migrants to get the

information they need for rational choice. Beyond this rather obvious point,

the question of the effectiveness of migration can be examined on three

different levels.

- The "efficiency of

migration" between any two areas is sometimes defined as the ratio of the net

flow to the total gross flow in both directions. In other words, if all

migrants go in the same direction, the efficiency is 100 percent, in the sense

that there is no cross-hauling of migrants: The net flow equals the gross flow.

At the other extreme, if the flows in the two directions just balance, so that

there is no net movement at all, the efficiency is said to be zero.

This measure may be useful in suggesting the degree to which a net migration

figure can be misleading as an indicator of the amount of movement; but it has

little to do with efficiency in any meaningful sense. People are not simply

interchangeable units of manpower, as the efficiency ratio implies. On the

contrary, those moving in one direction may be presumed to differ qualitatively

from those moving in the other; with each stream believing, and perhaps

correctly, that it is going in the right direction. Accordingly, a situation in

which two opposing flows largely cancel out in terms of numbers of people is

not necessarily indicative of any "lost motion" or waste in terms of either the

welfare of the individual migrants or the socially desirable spatial allocation

of manpower resources.

- A different and somewhat

more sophisticated question about migration is to ask whether it seems to be

going to the right places so far as the economic benefit to the migrant is

concerned. If we find people moving predominantly from places of lower incomes

to places of higher incomes, or from areas of heavy unemployment to labor

shortage areas, we surmise that they know what they are doing. If they go the

other way, or simply in all directions without any apparent regard to income or

employment differentials or any other obvious index of advantage, we have to

surmise either that the migrants are ignorant about the alternatives or that we

are ignorant about their real motivations.

Actually, most migration

flows do fit a "rational" pattern in relation to observable differences in

earning levels, unemployment rates, and such other easily identified variables

as climate and the level of public assistance benefits. Even the migration of

poor blacks from Southern farms to Northern city ghettos with high unemployment

and dismal living conditions can make sense in terms of improvement in the

migrants’ incomes, at any rate if we ignore possible adverse effects on

the social adjustment of the individuals and communities involved.

In

relating migration to indices of community economic welfare (for example, wage

or income levels) we cannot reasonably assume that the migrant immediately fits

into the pattern of the area and receives the average pay, employment security,

and other perquisites of the residents in his or her age and occupational

category. Migrants are no more representative of the populations of their

destination areas than they are of the populations of their areas of origin.

Some of their distinctive characteristics are subject to modification, so that

if they stay they will tend to become more similar to their new neighbors. This

tendency toward assimilation applies to skills, consumption patterns, ratings

on most kinds of "intelligence" tests, desired number of children, and social

behavior.

- Finally, we can judge

migration on the basis of how much it contributes to aggregate output or, more

broadly, to general social welfare. This is the appropriate level of judgment

for public authorities and public-spirited citizens to try to use. It calls for

assessing the effects of migration not just on the migrants but on the

communities they leave and enter.

This is by no means a simple

criterion to apply. On the face of it, the transfer of manpower to places where

its productivity is higher seems likely to raise national per capita output and

increase "aggregate welfare," insofar as that term has any meaning. And

differentials in real-earnings rates reflect, roughly at least, differentials

in the marginal productivity of labor. But migration (particularly highly

selective migration) can have important side effects (externalities) on the

areas involved, in terms of the costs of public services, the prospects for

future economic development, and the quality of life. The discussion of these

problems will be taken up in later chapters where we come to grips with the

processes of regional growth and change.

10.4 LABOR ORIENTATION: THE DEMAND FOR LABOR AT A

LOCATION

Our

discussion of mobility and migration has shed some light on what determines the

supply of labor at different places. To the extent that people move to places

offering more jobs or higher earnings, the labor supply adjusts to the spatial

pattern of labor demand. In areas where demand has grown relative to supply and

there are hindrances to inward migration, a tight labor market is manifest by

low unemployment rates and relatively high earnings; in places where labor

demand has declined or has failed to keep pace with the growth in the labor

force (resulting in part from natural increase of the population) and outward

migration is not easy, we find a labor surplus manifest in high unemployment

rates and relatively low earnings rates. This is, of course, a somewhat

simplified picture; many areas, at any given time, do not fit wholly into

either of these two contrasting categories.

On the

demand side, we envisage employers of labor as being concerned about its costs

and seeking to make profitable adjustments to such labor cost differentials as

they are aware of.

What, then,

will employers do if labor is expensive (relative to its productivity) in a

specific location? They have three possible ways of economizing on this

expensive labor: changing their production techniques so as to substitute other

inputs (for example, labor-saving machinery) for manpower; going out of

business; or moving to a different location where labor is cheaper. Where the

last two choices are seriously considered, we can say that the activity in

question is locationally sensitive to labor supply, or to some degree is labor-oriented.

The degree

of labor orientation varies widely among activities. In one extreme case

(activities tightly tied to a locality by market orientation, orientation to

inputs other than labor, or some other compulsion), labor costs may have no

significant locational effect at all—the employer’s demand for labor

at that location is highly inelastic. Retail trade and local services

illustrate this category of locally bound industries essentially unaffected by

labor cost differentials. If, for example, drugstore clerks were paid twice as

much in Milwaukee as in Akron, this would not induce Milwaukee drugstore

proprietors to relocate to Akron. Their market is entirely local. They are not

in competition with Akron in any sense and only need to assure themselves that

they are not paying their clerks more bounteously than their Milwaukee

competitors. There would, however, be a stronger incentive in Milwaukee than in

Akron to skimp on labor and substitute other inputs if possible. In the case

assumed, we might expect Milwaukee drugstores to be quicker to install such

things as vending machines, change-making cash registers, and display layouts

facilitating self-service.

At the

other extreme, we have strongly labor-oriented activities, those whose

demand for labor at any particular location is highly elastic—unless labor

is cheap, they will close down or go elsewhere. Normally, these are activities

that are rather footloose with respect to location factors other than labor

supply. A change of location makes relatively little difference in their costs

of transfer, level of sales, or outlays for other local inputs per unit of

sales, while their labor costs do vary markedly from one location or region to

another. Historically, the manufacture of textiles and standard clothing has

been strongly oriented to low-wage labor, while labor-intensive activities

requiring scarce special skills have been strongly oriented to the few places

where such skills are available.

Until

rather recently, most activities oriented to cheap labor as such mainly

employed unskilled or semiskilled blue-collar workers; but nowadays there are

numerous instances of firms moving to places where there is cheap white-collar

clerical labor. This is partly the result of the rapidly increasing proportion

of white-collar to total employment; but the locational effect also reflects

the increased availability of qualified clerical help in small

communities.

10.5 THE RATIONALE OF LABOR COST DIFFERENTIALS

Having

briefly considered the location of manpower from both the supply side and the

demand side, we now have some insight into the rather complex set of

interrelations shown schematically in Figure 10-3.

This diagram may be useful in reminding us of the interdependencies and tracing

the repercussions of different kinds of change. For example, the mechanism

implied by the concept of equalizing differentials in wages (that is, the

tendency of migration to eliminate real-income differentials) involves the

simple feedback sequence of effects shown by the solid lines in the

diagram below.

A more

complex and realistic model of the equalization process, taking into account

the fact that the price of labor affects living costs through the price of

locally produced goods and services, would include in addition the effects

shown by dashed lines in the same diagram. In either model, the

equalization effect is finished when there are no longer any real-income

differentials (that is, equilibrium has been reached, as far as the employee is

concerned). The reader may find it useful to trace out in a similar fashion,

using Figure 10-3 as a guide, what happens as

labor-oriented employers shift their hiring to areas of low labor

cost.

10.5.1

Where Are Labor Costs Low?

What are

the types of location to which a labor-oriented activity is attracted? There is

no single, simple answer to this question, mainly because different activities

and individual firms are seeking different kinds of labor cost economy. In some

jobs, one worker can perform as well as another. For such a job, labor is a

rather homogeneous input, and the wage rate is a good measure of labor cost. In

other occupations, skills and aptitudes vary widely, and a poor worker is not a

bargain at any wage. In some activities, the nature of the product, the type of

work, and the volume of output are highly changeable, and the employer wants to

be able to arrange with a minimum of difficulty for changes in job

specifications, short layoffs, overtime, and other changes. In such an

activity, good labor supply locations may be those where the local pool of

labor is large, where the average age and seniority of workers is low, or where

union bargaining has not built up a rigid structure of work rules.

Each

activity, then, will have its own preferences among labor supply locations,

determined by the relative emphasis it puts on low wages, skill or

trainability, and flexibility.

Low wages

are most often found in relatively backward areas where the demand for labor

has not kept up with the natural increase of the labor force. Obviously, these

are areas where manpower is impounded, as it were, by its imperfect outward

mobility. Less obviously, such areas tend to develop certain characteristics

that impede out-migration.

Many such

areas specialize heavily in kinds of employment for which the demand has grown

slowly or declined (for example, general farming or coal mining). This may, in

fact, be the chief reason why they are areas of labor surplus. But this

specialization also means that their labor force lacks experience in more

dynamic industries or occupations, which is a disadvantage in seeking work

elsewhere. There are attitudinal barriers, too, to giving up an occupation in

which one has acquired skill and seniority in order to start near the bottom in

a new trade. Derelict coal-mining villages in Appalachia are full of

middle-aged and older ex-miners who are slow to consider any alternative line

of work, even though it may be clear that the local mine is closed for good.

Finally, the very existence of a labor surplus and low wages helps to lower the

cost of such major budget items as shelter and services, and this helps to

diminish the economic incentive to move out.

The

advantages of experience and skill in a labor supply are most often found in

areas where the educational level is high and where activities requiring some

special skills have been concentrated for a long time. The supply of some types

of highly paid and scarce manpower (such as scientific and other specialists,

or persons of high artistic capability) is coming to be located increasingly in

areas and communities of high physical and cultural amenity, since those types

of people are in such demand that they can afford to be quite choosy about

where they are willing to live. It is no accident or whim that has located so

many advanced-technology and research-oriented activities in pleasant places

near major universities.

Flexibility

and diversity of labor supply are most likely to be found in a large labor

market in an intensively urbanized region, although one might surmise that the

rapid population growth of nonmetropolitan areas during the 1970s has increased

the diversity of labor supply in many less developed places as well. In some

large urban labor markets, however, the potential labor economies of size and

diversity are partly offset by the greater rigidity of union work rules and

bargaining practices, and the greater age and seniority of the work force that

characterize an area where an activity has developed a mature

concentration.

The

different kinds of labor cost advantage (low wage rates, skill, and flexibility

and diversity of supply) are unlikely to be found in the same places, because

to some extent they reflect contrasting area characteristics. Thus low wage

rates are associated with less developed areas having low living costs.

Experience and diversity of supply are often associated with the opposite type

of location: large urban areas in advanced industrialized regions having

relatively high living costs. Any given area, then, tends to be classified

according to the aspect of labor supply in which it has the greatest

comparative advantage.

10.5.2

Indirect Advantages of Labor Quality

The cost

savings involved in the use of highly productive (that is, skilled and/or

adaptable) manpower are sometimes underestimated, because not all of them show

up in labor cost per se. Recall the case of Harkinsville and Parkston discussed

in Chapter 2. Harkinsville workers work

faster, and get correspondingly higher hourly wages, than those in Parkston.

Thus there is no difference in labor cost per hour. Nevertheless, it will be

recalled, Harkinsville is a better location for the employer. For example, if

the output of the firm is to be 1000 units a day at whichever location is

chosen, the production worker payroll will be the same at either location; but

the plant can be smaller at Harkinsville. This means a smaller investment in

land and buildings; a smaller parking lot and cafeteria; fewer washrooms,

drinking fountains, and other facilities; a smaller work load for payroll

accounting and personnel management; and so on. Only such cost items as are

geared directly to the volume of output and not the number of people working

will be as large in Harkinsville as in Parkston: for example, production

materials, shipping containers, motive power and fuel for processing, and

loading and handling facilities.

10.5.3

Institutional Constraints on Wages and Labor Costs

To an

increasing extent in most countries, the supply of labor to an individual

employer at one location is affected by bargaining procedures and constraints

involving other employers and other locations as well. In activities where the

employing firms are few and large and where a strong labor organization

includes a major fraction of the workers, key negotiations can set a

quasi-national pattern of fringe benefits and work rules subject to only minor

local differences. Examples include the steel and automobile industries and

rail and air transportation. In still other activities, agreements cover major

sections of the activity (such as the East Coast ports with respect to handling

ship cargo).

Multiarea

bargaining introduces a strong additional equalization element into the wage

pattern. Even more generally, labor organizations with aspirations for

nationwide power try to work toward elimination of regional wage differentials.

Lower wages in areas of weaker organization are viewed as a threat to

employment in the areas of stronger organization and higher wages, since

employers are naturally tempted to move to save labor costs. And employers not

contemplating such a move are, of course, in favor of higher labor costs for

their competitors. Both parties, then, may well favor extension of the

geographical area of wage bargaining and the enactment of federal and state

minimum-wage laws, which limit differentials still further.

There are

often pressures toward similarity of pay rates and fringe benefit levels among

different activities and occupations within a single-labor market. This means

that if there are important high-wage activities in an area, they tend to some

extent to set the tone for related types of employment in the same area and to

make it generally a higher-cost area than it might otherwise be.

It is easy

to see how this works between occupations calling for similar qualifications,

so that the various activities in the community are competing in a common pool

of available workers with those qualifications. For example, steel workers are

relatively highly paid; as a result, a community dominated by steel making is

likely to have relatively high wage scales in construction and in other kinds

of employment not too different in their requirements from the jobs of many

steel mill employees. There would be no such direct effect, however, on wage

rates for sales or clerical workers.

Furthermore, unions of the dominant industry in a community generally

organize a number of other industries as well, the jurisdictional lines being

rather loose. Thus in Pittsburgh, metal fabricating plants are mainly organized

by the steelworkers’ union, while similar plants in Detroit have locals of

the automobile workers’ union. Though such a union does not necessarily

find it feasible or desirable to extend the wage and benefits pattern in the

dominant industry to the other industries it has organized in the same

community, there is certainly some pressure in that direction, and a consequent

reinforcing of the tendency toward intraarea wage level conformity.28

This

tendency is not area-wide, as a rule. For example, in the Pittsburgh labor

market area the upward wage pressures arising from the importance of some

tightly organized and high-paying industries are essentially restricted to

blue-collar occupations traditionally dominated by male workers, which heavily

predominate in the major industries involved. For many years, however,

Pittsburgh wages in retail trade and generally for jobs traditionally held by

women tended to be a little lower than those in cities of comparable size in

the same part of the country. Presumably, this reflected the relatively slow

growth of the area as a whole and the relative surplus of employable women

arising from the predominance of male jobs in the area. It is interesting to

note that in the late 1950s the differentials began to disappear, perhaps

reflecting vigorous local growth in office employment and no growth in heavy

industry employment.29

It has been

observed that the wage spread or skill margin among different occupations

within a single labor market is generally wider in less developed and slower

growing regions. This has been explained in terms of the lower educational

standards and the smaller proportion of semiskilled manufacturing jobs in such

areas, since education and the availability of an accessible "ladder" of skill

development both enhance occupational mobility and make the labor market more

competitive.30

A further

explanation lies in the tendency for people of higher occupational,

educational, and earnings levels to be geographically more mobile. As a result,

regional differentials in their earnings are narrower than is the case for

lower-status people.31In an area of labor surplus

and out-migration, it is the people in the better-paid occupations who move out

most readily; a relatively larger differential is required to move the

unskilled. The wage spread in such a labor market is consequently wide compared

to that in a more prosperous and active place.

10.5.4 Complementary

Labor

Different

categories of labor are to some extent jointly supplied; that is, the supply of

one kind of labor in an area depends on how much of the other kind is there. A

local population or potential labor force is almost always an assortment of

people of different ages, sexes, and physical and mental capabilities. If most

of the jobs available in the area call for superior aptitude, the area is

likely to have a surplus of people with more pedestrian abilities, and these

may represent a bargain in labor supply for an activity with less exacting

requirements. Conversely, if all the jobs in an area involve rugged manual

labor, there is likely to be a surplus of not quite so rugged individuals, who

might represent a bargain labor supply for an activity not requiring physical

strength.

We have to

consider, then, as another kind of advantageous labor location for an activity,

places where there is a heavy demand for some kind of contrasting and

complementary labor. This principle assumes, of course, that mobility is quite

imperfect, so that not all the different types of workers are able to seek out

the locations where their own kind of work is best rewarded.

The most

important basis for such restriction is inherent in family ties. In a

family’s choice of location from the standpoint of income, the most

important consideration is opportunity and earnings for the principal earner,

usually the head of the family. The spouse, and any other full or partial

dependents of working age, is then part of the potential labor supply in the

area where the principal wage earner locates. Accordingly, a labor market

heavily specialized in activities employing men is likely to have a plentiful

and relatively cheap female labor supply, and a labor market heavily

specialized in activities employing mature adults is likely to have a plentiful

and relatively cheap supply of young labor of both sexes.

Historically, many industries have owed their start in certain areas

to a complementary labor supply generated in such a way. A classic case is the

making of shoes in colonial days in eastern Massachusetts. The coastal area

north of Boston was heavily specialized in the male occupations of sailing and

fishing; this created a large complementary labor surplus of wives and

daughters, who were able to supplement family incomes by making

shoes—first at home and later in small factories.32 At a later period, the anthracite mining area of eastern Pennsylvania

attracted a substantial amount of the silk-weaving industry on a similar basis.

As late as the 1920s, it was observed that in the anthracite area about 60

percent of the silk weavers were women, while in the previous center of that

industry (in and around Paterson, New Jersey) 60 percent were men. The

manufacture of cheap standard garments, cigars, and light electrical equipment

and components also has historically been attracted to places offering

plentiful and cheap complementary labor.33

10.6 LABOR COST DIFFERENTIALS AND EMPLOYER LOCATIONS WITHIN AN

URBAN LABOR MARKET AREA

Up to this

point, we have been looking at the location of people and differentials in

earnings and labor costs on a macrogeographic scale, comparing labor markets as

units. A quite different set of considerations comes to the fore when we adopt

a microgeographic focus. Since the question of people’s residential

location preferences within urban areas has been dealt with in some detail in Chapters 6 and 7, we shall focus on the locational preferences

of employers as influenced by labor supply.

Although

labor market areas are in principle defined in terms of a feasible commuting

range, people prefer short work journeys to long ones, and as shown in Chapter 6, residential location decisions reflect

this and other access considerations. Thus the supply of labor to an employer

is not really ubiquitous throughout an urban area. Differential advantages of

labor supply within a local labor market are particularly significant when the

employer wants a special type of labor or a large supply of job candidates, and

in large labor market areas where residential areas are sharply differentiated

in character.

Thus if an

activity mainly employs a class of people dependent on public transportation to

get to work (for example, very low-income people or married people whose

spouses preempt the family car for their own commuting), it may have difficulty

in recruiting an adequate work force in the less accessible suburban areas.

Even if there is not an absolute shortage of applicants, there may not be

enough of a surplus of applicants to allow much freedom of

selection.

In the late

1950s, a study was made of the recruiting experiences of business firms in the

Boston metropolitan area which had relocated to sites along a circumferential

suburban freeway.34Most of the establishments in

the sample canvassed were sizable manufacturing plants, with electronics

equipment the most numerous category. Every firm in the sample had made an

advance survey of the residential and commuting patterns of its employees in an

effort to anticipate any recruitment problems that the new location might

involve. Several of the firms took explicit account of employee residential

locations in choosing the specific section of the highway on which to relocate.

Every firm found it necessary to establish a plant cafeteria at the new

location.

The

survey’s findings on recruitment problems were summed up as

follows:

A summary of the

observations of personnel managers interviewed indicated a general, but not

universal, conclusion that Route 128 locations in comparison with the downtown

areas definitely eased recruitment of engineering, professional and

administrative staff, but neither helped nor hindered recruitment of skilled

labor. Recruiting difficulties arose especially when the firms sought young,

female clerical workers, male unskilled workers, and seasonal workers, both

male and female, particularly in the higher income suburbs of the western

subarea of Route 128. The type of recruitment problem mentioned most frequently

was that of the younger, unmarried female, clerical workers.

The most

serious of the recruitment problems was that of unskilled production labor,

both male and female, but especially male, for seasonal work. Although this

problem did not arise frequently, the need for a seasonal expansion of

employment could cause a major headache for the personnel department, and

[seems?] to indicate very sharply the lack of a casual labor market in the

suburbs. At a downtown location, a firm could readily draw unskilled male and

female workers with a "Help Wanted" sign in the window for seasonal employment.

At a Route 128 location, this type of labor was scarce, and intown labor found

commuting to the plant time-consuming and costly for low-paying jobs on a

seasonal basis.

. . .The existence of a circumferential highway or of

a few long-distance commuters does not lead to the conclusion that there is

also a circumferential labor market, in which a firm at any one location can

draw equally well from any other part of the area. On the contrary it would

appear as if suburban firms tend to draw from areas nearby, and lose those

workers who live at abnormally long distances away.

. . .Relationship

of a firm to the immediate local labor supply seems to be crucial. Where the

local supply is already committed, or of the wrong composition to meet the

demands of the firm, the company will be forced to rely on longer-distance

commuters. If this means extension of commuting beyond the normal range, or

direction, for that type of labor, the firm will be likely to have major labor

supply difficulties)35

It has been more than a

quarter of a century since this report was published, but these findings are

still relevant. The area around Route 128 (now an interstate highway) has

become one of the nation’s major centers for advanced-technology

activities; and as the metropolitan area has grown, the labor market in the

vicinity of this highway has diversified substantially. However, the

recruitment problems described in the report’s summary are now

characteristic of firms considering locations on a yet more remote beltway

I-495 around the Boston metropolitan area.

More recent

and more elaborate studies have brought out some additional details concerning

the characteristics of urban labor markets, For example, Albert Bees and George

Shultz found in the Chicago labor market significant wage differentials for the

same occupation among different neighborhoods within the metropolitan area,

corresponding generally to the directions of commuter flow.36Similar differentials have also been identified on the

basis of distance from the central business district.37 The labor market of a large metropolis is clearly not a

single spatially perfect market in the sense that location within it makes no

difference.

As one

might expect, the least mobile types of manpower (low-skilled workers, members

of minority groups whose housing location choice is restricted by

discrimination, and secondary and complementary workers)38evince the greatest market imperfection in terms of

differentials in their net earnings after deducting commuting costs. This same

tendency toward wider geographical wage differentials for lower-income

occupational groups has already been noted at the interregional

level.

Workers are

attracted in their residential choices toward job locations, whereas employers

are attracted toward cheap labor supply. The relative force of these two sides

of a mutual linkage varies widely among occupations, of course. At one extreme,

the wage rate in an occupation is uniform throughout the labor market area, and

the commuters from more distant residential areas bear all of the extra money

and time costs of commuting over those greater distances. In the other extreme

case, the employers pay higher wages at job locations farther from employee

residential areas, absorbing the added costs of commuting longer distances by

paying compensating differentials in wages.39

The amount

of variation in wages in any given occupation will depend on the relative

mobility of the employees and the employers and also on the extent to which

union agreements or understandings among employers impose a single wage

standard for the whole labor market area. It will depend also on two factors

already mentioned; namely, the skill and income level of the occupation itself

and the extent to which the workers’ residential choices are limited by

discrimination.

It is clear

that the spatial imperfection of large urban labor markets affects particularly

the low-income worker. One of the most serious aspects of the present-day

problem of inadequate job opportunities for residents of urban slums is that an

increasing proportion of the kinds of jobs they might fill has shifted to

distant suburban locations with little or no public transportation available,

while very few employers have been willing to accept some obvious disadvantages

of a slum location for the sake of closer access to that labor

supply.

10.7 SUMMARY

Several

kinds of spatial differentials in earnings and income are of interest to

various parties. The relative opulence of two communities can be compared in a

marketing survey in terms of total or per capita money income. An individual

looking for a good place to work would be interested in wage rates or annual

earnings in his or her specific occupation, adjusted for any differences in the

cost of living. An employer looking for low labor costs would want to compare

specific wage scales, adjusted for productivity and fringe benefits.

Relative

pay levels in specific occupations in the United States show a pattern of

interregional differentials, with lower levels in the South and in smaller

labor markets. These two differentials (North-South, and size of place) appear

also in measures of per capita annual income and living costs. Income and pay

levels deflated by cost-of-living indices seem also to show similar patterns,

but to a much smaller degree. The term "equalizing differentials" is applied to

a differential in money wages or income that merely compensates for a

cost-of-living differential.

People move

in response to perceived differences in prospective real incomes as well as

other factors; migration flows depend on the characteristics of both the origin

and the destination areas, the difficulties of the journey, and the

characteristics of the migrant. Within a labor market area, housing and

personal considerations account for most moves; for migration between labor

market areas, job-related reasons are the most important.

The cost